Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.4 - Winter 2009

Editor of this issue: Danguolė Kviklys

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.4 - Winter 2009 Editor of this issue: Danguolė Kviklys |

Early Orthographical Struggles of the Lithuanian Daily Newspaper Draugas

AURELIJA TAMOŠIŪNAITĖ

Aurelija Tamošiūnaitė is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Slavic & Baltic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her scholarly interests include the sociolinguistic history of the Lithuanian language, the history of standard languages, sociolinguistics, and the Lithuanian language in the United States. She has published several articles in the annual historical sociolinguistic journal Archivum Lithuanicum and in Lituanus.

ABSTRACT

The objective of this article is to examine the orthographical

practices that were followed in the first issues of Draugas (July 1909

– December 1909), as well as to explain orthographical

struggles with the Lithuanian alphabet that occurred because of the

lack of some Lithuanian letters (<ė>, <į>,

<ū>, and <ų>) at the newspaper’s

Slovak printing house, Bratstvo. An analysis revealed that in those

early issues, three orthographical models were followed in the

newspaper. The editors of Draugas

were aware of the orthographical

shortcomings and tried to use other diacritical letters in place of the

missing ones. However, in practice, the printers did not always follow

the editors’ instructions. Therefore, the orthography of the

newspaper was much more diverse than the editors expected.

In 2009, the American Lithuanian Roman Catholic daily newspaper Draugas celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary. These one hundred years of publication represent not only a century-long history of the American Lithuanian press, but also a history of the Lithuanian language in the United States. An analysis of the orthography1, lexis2, grammar, and syntactic structures in Draugas provides interesting insights into the history of the Lithuanian language among emigrants and the development of Standard Lithuanian3 on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean.

There have been several attempts to analyze the language of Draugas (Macevičiūtė 2000; Miliūnaitė 2006); however, none of them were devoted solely to this newspaper. Macevičiūtė (2000) analyzed language attrition among both Full Lithuanian (native Lithuanian) and American Lithuanian speakers based on written and spoken registers. The data that represented written American Lithuanian were taken from Draugas. Miliūnaitė (2006) analyzed the usage of borrowings4 in Lithuanian newspapers published in emigration. Draugas was one of several newspapers published in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland that she analyzed. However, both of the above-mentioned studies focused on contemporary linguistic practices in Draugas, and were limited to the usage of borrowings, specific features of grammar, and syntax. An analysis of the orthographical practices of the very first (1909) issues of Draugas (i.e., a historical approach) has not yet been undertaken.

In fact, there have been few linguistic studies that focused on the language of American Lithuanian newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century. Subačius (2004) analyzed double orthography in American Lithuanian newspapers from 1898 to 1907. He studied the introduction of the letters <č> and <š> to the American Lithuanian press by reviewing eight newspapers: Vienybė Lietuvninkų, Lietuva, Viltis, Darbininkų viltis, Tėvynė, Žvaigždė, Katalikas, and Saulė 5. The use of graphemes6 <č> and <š> to denote the sounds [č] and [š], English <ch> and <sh>, respectively, was recommended to Lithuanian newspaper editors by Vincas Kudirka in Statrašos ramsčiai around 1890 (Subačius 2004, 190)7. However, most Lithuanian Catholic newspapers continued to use the digraphs <cz> and <sz> until 19018 (Venckienė 2007, 149). Subačius’s analysis revealed that the majority of American Lithuanian newspapers had implemented the use of the letters <č> and <š> by about 1904 (Subačius 2004, 198). According to Subačius, “the early acceptance of standard orthography by the American Lithuanian newspapers also implies that the Lithuanian community in America became accustomed to that previously unusual standard in approximately four and a half years. ... The standard was accepted in America before the beginning of massive free publication in Lithuania.” (2004, 199–200) This was a very important turning point in the development of Standard Lithuanian. The standard orthography was accepted within three years of the publication of Jonas Jablonskis’s Lithuanian grammar in Tilžė, East Prussia, in 1901.

Printing problems

The first issues of Draugas were printed by a Slovak printing house, called Bratstvo, located in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. However, neither the publishers of Draugas nor the paper’s editors were satisfied with the Slovaks’ work. Those first issues were printed without several important Lithuanian letters. In addition, because the printers did not understand the Lithuanian language, they made many glaring mistakes. For example, the first issue of Draugas contains such misspellings as garski instead of garsi (famous); persiuntinnu instead of persiuntimu (shipping); Graugas instead of Draugas (Friend, the name of the newspaper); gyvenami (livable) instead of gyvendami (living); and preitais instead of praeitais (previous). Although typographical errors are inevitable in any printing job, the possibility of misspelling words increases when the printer does not understand the language. The Slovaks complained that they were not given sufficient time to print the newspaper in a language they did not understand, while the Lithuanians were dissatisfied because of the number of errors and the unwillingness of the Slovaks to cast the missing Lithuanian letters for their presses.

The problems arising from the missing Lithuanian letters were explained in an unsigned editorial on September 9 (pg. 120). The editors wrote:

|

Buvo manoma vietinėje slavokų spaustuvėje teišleisti tris pirmuosius numerius – bet išėjo kitaip. Slavokai sakėsi turį visus lietuviško rašto ženklus, tečiau, kuomet pirmas numeris tapo sustatytas ir prisiėjo daryti korektą, pasirodė, kad truksta trijų labai svarbių raidžių: „į“, „ų“ ir „ė“. Prisėjo padaryti vieną iš dvejo: arba sustabdyti pirmą numerį arba jį išleisti teip, kaip buvo sustatytas. Tapo išrinktas antras kelias. Padėjome atsakomą pasargą ir prižadėjome tolesnius numerius parupinti trukstančias raides. Norėjome duoti jiems laiko tatai padaryti ir tyčia pasivėlinome su antruoju numeriu. Bet atėjus laikui daryti korektą, pasirodę tas pat. Spaustuvininkai teisinosi tuo, kad nežinoję, kas mokėsiąs už naujus rašto ženklus. |

It was originally intended that only the first three issues would be printed in the local Slovak printing house; however, it turned out otherwise. The Slovaks had claimed to have all the necessary Lithuanian characters, but when the first issue was typeset and we proofread it, it became obvious that three very important letters – “į”, “ų”, and “ė” – were missing. We had two choices: either to stop the first issue, or to print it the way it had been set. We chose the second option. We added an explanation and promised to print future issues with the required characters. We wanted to give them [the Slovaks –A.T.] more time, so we were purposely late with the second issue. However, when the time came to do the proofreading, the situation was the same. The printers made the excuse that they did not know who would pay for the new characters. |

| Tuo tarpu pasivėlinta su savosios statomos mašinos (linotypo) ir kitų, reikalingų spaustuvei daiktų atėjimu. Slavokai skundėsi, kad neturį laiko statyti laikraštį nesuprantamoje kalboje. Redaktoriui reikėjo visą pristatomą medžiagą pačiam pirmiau atspausti su rašomaja mašina (typewriter) – ir tai statytojai pridarydavo klaidų eibes. Buvo daug gerų norų, daug darbo – bet rezultatas gal niekam teip nebuvo skaudus, kaip leidėjams ir redakcijai. | At the same time, the arrival of our own printing machine (a linotype) and other necessary printing materials was delayed. The Slovaks complained that they did not have time to typeset a newspaper in a language they did not understand. Our editor himself had to first type all the material we were submitting on a typewriter – and even then the printers made many mistakes. There were a lot of good intentions, a lot of work; however, there was probably no one for whom the results were more disappointing than for the publishers and editors. |

| Už kiek laiko pasirodė, kad spaustuvėje esama raidės „ė“, tik su brukšneliu vieton spaugelio viršuje. Pradėjome tuojau ją vartoti, o kad parodyti, jog neesame jau tokiais lietuviškos rašybos nežinovais, liepėme „į“ ir „ų“ paženklinti kaip norits – jei ne iš apačios, tai bent iš viršaus. Tokiu budu ant raidžių atsirado daugybė akcentų, kurių prasmė buvo suprantama redakcijai ir statytojams, bet kurie šeip-jau žmoneliams išrodė ir juokingi ir... paslaptingi. | After a while, it became clear that the printing house had the character “ė,” except that it included a macron [-] instead of a dot above [the letter]. We began using it right away. To show that we are not so ignorant about writing in Lithuanian, we asked them [the printers] to identify the letters “į” and “ų” in some way – if not at the bottom, then at the top [of the letter]. This led to the addition of a lot of accent marks to the letters, and though their meaning was clear to the editors and printers, to general readers, they appeared both funny and … mysterious. |

It is clear, then, from

the editorial that the orthographical struggles

with the Lithuanian alphabet were due to the lack of several characters

representing Lithuanian letters at the Slovak printing house, and to

the reluctance of the printers to typeset the newspaper in a language

they did not understand. The editors were aware of these orthographical

shortcomings, and in the very first issue of Draugas (pg. 8),

they

published the following notice:

| Neatejus lietuviškoms raidems i laiką, šitas „Draugo” numeris tapo atspaustas be kai kuriu lietuviškojo rašto ženklu. Tolesni numeriai eis priderančiai. | Because [certain] Lithuanian characters did not reach us in time, this issue of “Draugas” was printed without them. Future issues will be published properly. |

This notice was repeated in the second and third issues. In the fourth

issue, after substitutes for the missing letters had been found, the

note no longer appeared. However, in the fifth issue (pg. 77), the

readers found:

| ATSISAKUS [sic] SLAVOKÚ SPAUSTUVEI STATYT TOLIAU MUSÚ LAIKRAŠTÍ – DÉLEI DARININKÚ [sic] TRUKUMO – ŠITAS “DRAUGO” NUMERIS IŠEINA ANT GREITOSIOS SEKANTÍ NUMERI TIKIMÉS IŠLEISTI IŠ SAVOSIOS SPAUSTUVÉS. REDAKCIJA | Because the Slovak printing house has refused to continue printing our newspaper due to the inability of its workers, this issue of “Draugas” was published in a hurry. We expect to print the next issue in our own printing house. Editorial Board |

The solution that the editor referred to in his editorial of September 9 was presented in the fourth issue: instead of <ė>, the editors used <e> with a macron above the letter, while <į> and <ų> were indicated with a mark “at the top.” However, in practice, this rule was not always followed. Therefore, the objective of this article is to examine which orthographical practices were actually followed in the first issues of Draugas (July 1909–December 1909); what deviations from the standard orthography (i.e., the one codified by Jonas Jablonskis) can be observed; and how they can be interpreted.

Orthography

From July 1909 to December 1909, three different orthographical practices were followed. The first three issues of Draugas (July 12, July 26, and August 7) were printed without four Lithuanian letters that belong to the standard orthography: <ė>, <į>, <ų>, and <ū>. Instead, the letters <e>, <i>, and <u> (for both <ų> and <ū>) were used. For example (translation and July 12 issue page number are indicated in parentheses):

a)

<e>: apgynejo

(defender’s, 2); gatveje

(in

the street, 3); numire

(died, 2); prasidejo

(began, 2); tikejimo (of

the faith, 3);

b) <i>: itekmingu

(influential, 2); ji

(him, 5);

negrišta

(does not return, 3); Šimet

(this year,

7);

c) <u>: kataliku

(Roman Catholics’, 1); keleriu

(several, 2); kitu

(others, 2); lietuviu

(Lithuanians’, 1);

metu

(years, 2); rupintusi

(would take care of, 2); tamsus

(dark, 2);

truksta (is

missing, 2).

However, in the fourth issue of Draugas (August 12), new graphemes were introduced to replace the missing letters <ė>, <į>, and <ų>. The characters <ē> and <é> were used as substitutes for the letter <ė>; the character <í> was substituted for <į>; and the character <ú> was substituted for <ų>. For example (translation and page number are indicated in parentheses):

a) bendrovēs

(cooperative’s, 53); ēmējai

(participants, 53);

kalbēta (it

was discussed, 53); nagrinējo

(analyzed, 53); pasiekē

(reached, 63); pradējo

(started, 60); užmokēti

(to pay), 53;

b) apylinkés

(area’s, 55);

apsiémé

(undertook, 55); gyné

(defended, 55); mégéjus

(amateurs, 55);

netikétos

(sudden, 55); senovés

(of ancient

times, 55);

c) ípēdinis

(descendant, 50); jí

(him, 50);

kurí

(which, 50); patí

(oneself, 50);

revolverí

(revolver, 50); tokí

(this kind, 51);

d) ilgú

(long, 58); jusú

(your, 58);

keturiú

(four, 50); mokytú

(educated, 58);

musú

(our, 56); paragavusiújú

(those

who have tasted, 58); smukliú

(pubs, 58);

šeimynú

(families, 58); tú

(those,

58); visú

(all, 51).9

The substitution of two characters – <í> for <į> and <ú> for <ų> – was consistent throughout the issue. However, the substitution of other characters for <ė> was not. As noted previously, the printers were instructed to substitute <ē> for the missing letter <ė>. And indeed, <ē> is used in the majority of the articles in the fourth issue (pp. 49–51, 53, 56, 59–64). However, it appears that the compositors may have substituted a variety of pi matrices. In some articles, they used the characters <é> or <e>. Part of the article “Kazimierininkai” on p. 52 was printed using <é>; however, the end of the same article on p. 53 uses <ē>. This may indicate that the text of the article was set by two different compositors simultaneously, with each choosing different characters to substitute for <ė>. On the other hand, because these accented characters were not part of the standard Linotype keyboard layout and had to be inserted and then later sorted out by hand, the compositor may have run out of one accented character and replaced it with another to save time.

The article “Visuotinas Lietuviu mokslo draugijos susirinkimas” on pp. 54 and 55 is printed again with <é>, while the articles “Lekcija,” “Evangelija,” and “Juokai” on p. 55 are printed without any diacritical mark on <e>: ítikejote (believed), numire (died), prisikele (rose from the dead), uždetú (would place on), and others. <E> without any diacritical mark is used on both p. 58 (throughout the column “Iš Lietnvišku [sic] dirvu Amerikoje”) and on p. 59. The typesetters may have used all the matrices for both characters, <ē> and <é>, and started using <e> instead of sorting out the matrices for the pi characters. The sequence of substitutions for the letter <ė> thus occurred as follows: first, the compositors replaced <ė> with <ē> (as requested by the editors); then, with <é>; and finally, possibly because they were rushed and the insertion of special characters considerably slowed their progress, they used <e> without any diacritical mark above it.

On the other hand, the inconsistency in the use of <ē> and <é> indicates that the compositors tried to substitute other characters with diacritical marks for the missing Lithuanian letter <ė>. This attempt demonstrates the first level of diacritical perception – the printers realized that a diacritical mark was needed (because the editors of Draugas had asked them to use one); however, the type of diacritic was not important to them.10 This inconsistency may have occurred for several reasons:

a) the

article texts were set by different Slovak compositors, and not

all of them knew what character should be used as a substitute for

<ė>;

b) the compositor was rushed by deadline pressures and did not have the

time to insert (and later sort out) the matrices for these special

characters;

c) each typesetter for the newspaper may have had his own slightly

different collection of matrices; therefore, if an article was set by

two different typesetters, each may have applied a different strategy

in substituting characters in the article.

The fifth issue of Draugas (August 19) was printed in the same manner as the fourth – by using <ē>, <í>, and <ú> as substitutes for the missing Lithuanian letters. It is important to note that the entire issue was printed using the character <ē>; <é> was used only in headlines, which were set mainly in upper case type – VIETINÉS (of the local, 71); TÉVÚ MEILÉ (parents’ love, 76) – or in type of a different size.

Although throughout the fourth and fifth issues other diacritical letters were used in place of <ė>, <į>, <ų> (and sometimes <ū>), the advertisements on the last page of the newspaper were always printed with no substitutions for the missing Lithuanian letters; for example, LIETUVIU (Lithuanian, 64); FABIOLE (fable, 64); egzemplioriu (copy, 64); Vaiku (children’s, 64); siuskit (send, 64). This indicates that the printers did not change the orthography of the advertisements, but rather reused the same type set for several issues. Even the typographical errors remained the same in all five issues: Garski instead of Garsi (famous), persiuntinnu instead of persiuntimu (shipping). Only one error, which appeared in the first issue (Graugas instead of Draugas), was corrected in the second issue.

The sixth issue of Draugas (August 26) was printed using standard Lithuanian orthography; i.e., the previously missing Lithuanian letters <ė>, <į>, <ų>, and even <ū> were used throughout the text. For example: aplėkė (ran around), būdu (the manner in which), dešimtį (ten), įširdę (angry), ištikrųjų (indeed), mėnesių (months), mokėtų (would pay), tąjį (that one), ūkio (household), and valstybės (nations). Other issues from July 1909 to December 1909 were printed using standard orthography, with no variations.11

The variations in orthography in the fourth and fifth issues of Draugas indicate that in practice, substitutions for the missing Lithuanian letters were more complicated than the editors indicated. Although <í> and <ú> were substituted for the letters <į> and <ų> quite consistently, substitutions for the letter <ė> were inconsistent. The editors indicated that they had asked that the Lithuanian letter <ė> be replaced by the character <ē>. However, the Slovak printers used not only <ē>, but also <é> and <e>. Therefore, in practice, the editors’ instructions were not followed.

Usage of the letter <ū>

The editors of Draugas did not include the letter <ū> in the list of missing letters. However, in the sixth issue, it was used, along with the other previously missing Lithuanian letters <ė>, <į>, and <ų>. There may be several reasons why <ū> was not originally mentioned.

First of all, the usage of <ū> was very inconsistent in Draugas during the period analyzed. To signify the long [u], the letters <u> and <ū> were both used, often in the same words: budas and būdas (manner), Prancuzijos and Prancūzijos (belonging to France), musų and mūsų (our), burelis ir būrelis (small group), būti (to be), būtų (would be), būsime (we will be), busiąs (he will be), and buk (be). This variation, which began in the sixth issue, occurred in all the issues of Draugas that I analyzed.

The irregular usage of <ū> may be related to the uneven introduction of this grapheme into Lithuanian standard orthography at the turn of the twentieth century. The letter <ū> was accepted into standard orthography only after long discussions. Initially, the letter was introduced by Jablonskis in several articles that appeared in Varpas in 1892. In the same newspaper in 1893, Jablonskis published several articles in which he discussed why the letter was needed in Lithuanian orthography (Venckienė 2007, 118). Finally, <ū> was codified in his Lithuanian grammar of 1901.

According to Venckienė, the letter <ū> began to be used more regularly in Lithuanian Catholic newspapers as early as 1894 (Žemaičių ir Lietuvos Apžvalga) and 1900 (Tėvynės sargas, Žinyčia). The secular press only started using it more regularly in 1903 (Varpas, Naujienos, Ūkininkas) (2007, 149). However, according to Palionis, even after the publication of the Jablonskis grammar, the usage of long <y> and <ū> were not regular: some authors wrote phonetically (with <y> and <ū>), while others wrote traditionally (with <i> and <u>) (Palionis 1995, 242). This inconsistency over the use of <ū> was still present in Draugas in 1909, indicating that the editors (perhaps the authors as well) either were not sure when they should use <ū> or simply had not changed their writing habits.

From the very beginning, Draugas reprinted some articles in its column “Iš Lietuvos” from the Lithuanian newspaper Viltis12. In the texts taken from Viltis, the usage of <ū> is quite regular and consistent with the original: aptrūnijusios (rotted, 271); būsimosios (the future, 271); būti (to be, 272); mūrinės (stonework, 271); mūro (of stone, 272); mūsų (our, 271); ūkininkauti (to farm, 271); and ūkio (farm, 271). However, in the same issue of Draugas, <ū> is not used in the editorial: buk (be, 276); butų (would be, 276); krutine (breast, 276); literaturos (of literature, 276); musų (our, 276); and nebutų (would not be, 276). The same pattern occurs in the local news: buk (be, 275); butent (precisely, 275); butų (would be, 275); grudų (grain, 275); sunaus (son’s, 275); but būti (to be, 275); kariūmėnė [sic] (army, 275); neapsižiūrėjimą (oversight, 275); and prižiūrėti (to look after, 275). This indicates that the regular usage of <ū> in Draugas appeared only in reprinted texts from Lithuania, while in the local news and editorials, the usage was not consistent – the writers may not have been sure when to use the letter <ū>. It seems that the editors of Draugas considered the letter <ū> to be the least necessary Lithuanian letter.

Consistency or variation?

Does the variation in orthography described above indicate that the editors and publishers of Draugas were not concerned about consistency? It is evident from several editorial notes that the editors were not satisfied with the variations in orthography. On January 13, 1910 (pg. 25), the article “Kalbos reikaluose” (On Matters of Language) is followed by a brief editorial remark:

| Redakcijos prierašas: – Abejojame apie teisingumą išvadžiojimų apie “pakuta” ir “gyvonį”, bet spauzdiname šitą raštelį, dėlto kad netikrumas rašybos ir kalbos slogina lygiai skaitytojus, kaip ir raštininkus. Lai komisija sutvarkyti kalbos ir rašybos dalykus kuoveikiausiai [sic] apskelbia savo darbo vaisius! | Editorial remark: – We doubt that the explanations of “pakuta” and “gyvonis” are correct. However, we have published the article because [we know that-AT] uncertainties in writing and language concern readers as well as writers. Let the commission for resolving language and writing matters announce the fruits of its labors as soon as possible! |

The note indicates that the editors of Draugas were not satisfied with the irregular orthography and that they sought consistency. Jablonskis’s grammar, which codified many language norms, did not solve all orthographical issues. In practice, even after 1901, orthography varied greatly (Palionis 1995, 240-243). On January 20, 1910 (pg. 40), yet another complaint about constant variation in “our language” appears in an editorial:

| <…> Musiškių Bugos ir Jablonskio kalba daug sunkesnė ir mažiau suprantama nekaip, padekime, Kudirkos. Kaip kadą nei patįs kalbininkai nežino, ką daro. Buvo įvedę “velionį”, tasai žodis buvo jau prigijęs musų kalboje ir literaturoje – tik štai tapo atrasta, kad “velionis” negerai nukaltas, kad reikia grįžti prie “nabaštiko” (kiti rašo “nabašninkas”, dar kiti “nabaštininkas”.) Išvarė iš kuno dušią, pavadino ją “vėle”, kunui davė “sielą”, – o dabar jau atranda, kad “dušia” geresnė už “sielą” ir “vėlę”. “Mylista” buvo apskelbtas slavišku žodžiu, bet p. Buga pagarsino jį esant lietuvių kalbos turtu. Na, tai dabar žmogus ir žinok, kaip rašyti! |

<…> The language of our [compatriots-AT] Buga and Jablonskis is much more complicated and less clear than, let’s say, Kudirka’s. Sometimes even linguists themselves do not know what they are doing. They introduced “velionis” [the deceased], a word that was accepted into our language and literature; however, it was determined that “velionis” was not formed in an appropriate manner, and that therefore, we need to go back to “nabaštikas” (some write it as “nabašninkas,” others, “nabaštininkas”). They drove “dušia” [soul] from the body, named it “vėlė,” gave the body a “siela,” and now they are finding that “dušia” is a better word than “siela” and “vėlė.” “Mylista”[you (formal)] was denounced as a Slavic word, but Mr. Buga proclaimed that it is a treasure of the Lithuanian language. So now, how is a person supposed to know how to write? |

| Pirmiau rašėme “mes”, “šįmet”, “linksmins”, “gyvens”, “lyja”, “avys” – ir buvo gerai. Kriaušaitis liepė pridėti visokių ženklų iš viršaus ir apačios, vienur išmest nereikalingas raides, kitur įsprausti į tarpą. Paklausėme. Dabar vėl revoliucija. Kriaušaitis negeras, Jaunius negeras, Baranauskas negeras – niekas negeras. Et, jau kas-kas, bet “Saulė” turi gerą progą pasiteisinti iš to, kad yra pasilikusi “civilizacijos” užpakalyje! | In the past, we wrote “mes,” “šįmet,” “linksmins,” “gyvens,” “lyja,” “avys” – and it was fine. Kriaušaitis told us to add all kinds of marks to the top and bottom, to eliminate unnecessary letters in some places and to add others in other places. We obeyed. Now there is another revolution. [They say that-AT] Kriaušaitis is bad, Jaunius is bad, Baranauskas is bad – everyone is bad. Well, only “Saulė” has the right to justify itself, on the grounds that it has lagged behind “civilization”! |

The note cited above

refers to both lexical and orthographical

variations. It is a good example of the linguistic situation at the

beginning of the twentieth century: a non-uniform orthography and

discussions about borrowings, the introduction of new words, and

reforms of writing. On the other hand, it is evident that the editors

and publishers of Draugas,

like their colleagues in Lithuania, were

concerned about orthographical uniformity; i.e., a standard of writing.

They were familiar with the situation in Lithuania and tried to apply

the new rules in Draugas.

Ironically, the most conservative American

Lithuanian newspaper, Saulė,

is mentioned at the very end of the quote. Saulė did not apply

standard orthography and, even in 1907, was

still set with Polish orthographic characters (Subačius 2004, 201).

Therefore, according to the editors of Draugas, it did not

have to deal

with rules that were constantly changing.

Conclusions

1. An analysis of several of the earliest issues of Draugas (July–December 1909) revealed that at the very beginning, three orthographical models were followed in the newspaper: a) the first three issues of Draugas were printed without the Lithuanian letters <ė>, <į>, <ū>, and <ų>; b) the fourth and fifth issues were printed with the characters <ē>, <é>, <í>, and <ú> as substitutes for the missing graphemes <ė>, <į>, and <ų>; c) starting with the sixth issue, all other issues of Draugas were printed using standard orthography; i.e., the letters <ė>, <į>, <ū>, and <ų> were used.

2. The irregular usage of the letter <ū> in the first issues of Draugas indicates that the editors – and perhaps the authors – were not sure when to use the letter, and quite often the long [ū] was represented by both <u> and <ū>. This suggests that the editors of Draugas considered <ū> to be the least necessary Lithuanian letter.

3. The inconsistent usage of <ē> and <é> as substitutes for the missing letter <ė> may have occurred for several reasons: the type was set at different times; deadline pressures may have forced the typestters to skip inserting the special characters by hand; the copy was set by different typesetters, who may not have known how to substitute for <ė>; each of the newspaper’s typesetters may have had his own slightly different collection of characters. So, if an article was set by two different typesetters, we can trace different strategies applied to the selection of diacritical characters in the same article.

4. Orthographical struggles with the Lithuanian alphabet occurred because of the lack of some Lithuanian letters at the Slovak printing house Bratstvo, and because of the unwillingness of the printers to set a newspaper in a language they did not understand. The editors of Draugas were aware of the orthographical shortcomings and tried to use other diacritical letters in place of the missing ones. However, in practice, the printers did not always obey the instructions of the editors. Therefore, the orthography of the newspaper was much more diverse than the editors anticipated.

5. The editors of Draugas sought orthographical consistency in writing and tried to follow the orthographical practices that were accepted in Lithuania. This was a conscious decision that indicates that the newspaper Draugas in the United States actively participated in and supported the process of language standardization in Lithuania at the beginning of the twentieth century.

I would like to express my gratitude to Jurgis Anysas and Jonas Kuprys, who made copies of some of the issues, Prof. Giedrius Subačius and Dr. Dalia Cidzikaitė for their insightful comments, and Kristina Vaičikonis for her help in editing this article.

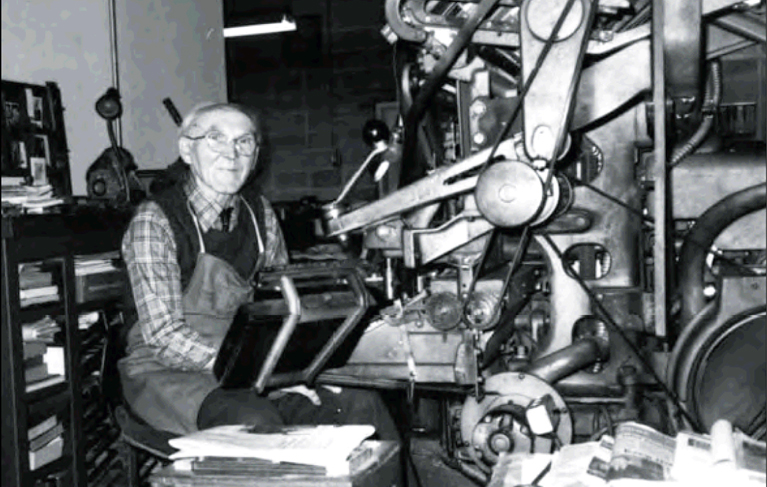

Marian Brother Vincas Žvingilas (1908 –1997) was the heart of Draugas. He worked there for forty-five years and operated the Linotype as well as other press equipment. |

Draugas.

An American Lithuanian newspaper. Analyzed issues (July 1909

– January 1910) were borrowed from the Lithuanian Research

and Studies Center, Chicago, Illinois, and the Draugas archive,

Chicago, Illinois.

Macevičiūtė, Jolanta.

“The Beginnings of Language Loss in Discourse. A Study of

American Lithuanian.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Southern California, 2000.

Martynas Mažvydas National Library

of Lithuania, Electronic Catalogue – www.libis.lt (accessed

June 25, 2009).

Miliūnaitė, Rita. ,,Sava ir

svetima išeivijos žiniasklaidos kalboje” (The

Native and the Foreign in the Language of Emigrant Media). Synopsis of

a paper presented at a Lithuanian emigrant press seminar in 2006.

http://www.kalbosnamai.lt/images/dokumentai/sava_ir_svetima_iseivijoje_2006.pdf

(accessed June 23, 2009).

Palionis, Jonas. Lietuvių rašomosios

kalbos istorija (A History of the Written Lithuanian

Language). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla, 1995.

Subačius, Giedrius.

“Double orthography in American Lithuanian Newspapers at the

Turn of the Twentieth Century,” in Studies in Baltic and

Indo-European Linguistics. In Honor of William R. Schmalstieg,

edited by Philip Baldi and Pietro U. Dini, 189–202.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2004.

Venckienė, Jurgita.

“Lietuvių bendrinės kalbos pradžia: idėjos ir jų sklaida

(1883–1901)” (The Beginnings of Standard

Lithuanian: Ideas and Their Dispersion, 1883–1901). Ph.D.

dissertation, Vilnius University, 2007.